Chord progressions are not just random occurrences; they follow a logic that’s deeply related to the concept of chord families.

Yes, have you ever noticed how some people can just listen to a song once and start playing it immediately? How do they know what chord is coming next?

Well, that’s not ancient magic or a natural-born skill; it’s theoretical knowledge you can learn too. Indeed, if you know what family of chords the song is using, you can make out what’s coming next.

If this is a skill you always wanted to learn, let me tell you that you’re in the right spot; I’m going to pass this information to you in just some paragraphs.

Plus, we’re not going to go around the bush, we’ll see road-tested, proven tips so you can learn chord families fast and be playing them in no time.

So, are you ready to be a music magician?

To learn chord families quickly, you should use information chunking, start with the CAGED system and work on one family at a time. Also, you should play every family at least 8 to 10 times a day, list down three songs to learn per family, and break the chords down into single notes.

Moreover, every time you practice you should break the 20-time limit, allow time between repetitions, sleep on the information, and play them consistently with a plethora of chord progressions.

That was the sneak peek at the cataract of information coming your way. You’re about to read the ultimate guide to learn everything you need to learn about chord families and use them in a myriad of scenarios.

We need a cauldron, feathers, the hair of a giant, and the tail of a rat besides a wand and a purple toga.

Just kidding, bring pen and paper, and your favorite guitar because you’re about to learn a powerful new skill in theory and also in practice.

Ready or not, here we go!

What are chord families in music?

Chord families are, in very simple terms, related chords that sound well together.

As a musical principle, any given chord can be followed by any other given chord. Yet, some chords sound better together.

I know what you’re thinking: Duh!

Yet, this is not a minor detail, it is one of the main reasons why learning this is paramount for your future as a musician.

It’s not that chord families were created as a concept to organize music. On the contrary, music was already organized this way simply because our ears have been putting these chords together for centuries.

Calling them “chord families” is just unveiling and giving a new name to the gears that have been making music happen for years.

So, chords in chord families are related to each other in a manner that makes them sound well together. We’ll see, in this article, more than one way to organize them and the many ways to take advantage of this knowledge.

Benefits of Learning Chord Families

Let’s take a look at the benefits of learning chord families:

- As a shortcut – Whether you’re trying to learn a new tune you just heard or create your own songs, knowing chord families can help you discover where the song should go next. Yes, in this case, information replaces the trial-and-error approach; so, instead of moving blindly in musical darkness, you get a compass or a lighthouse.

- In harmony – Besides chords, learning how these families work can help you understand harmony better. This can be a great gateway to making better solos and writing melodies that are closer to the song, and, therefore, better sounding.

- For jamming – When improvising on the stage of a jam, for example, you can be one step ahead if you know chord families because you have an idea where the music is going. Therefore, whether you’re playing base or soloing over it, you can make better use of the nuances and bridge notes to engage the wow factor with what you’re playing.

These are just three of the many benefits you’ll find after you’ve learned chord families.

Perhaps the biggest benefit of them all is that this knowledge will take your playing to the next level.

How many chord families are there on the guitar?

There are 12 notes in the musical alphabet. Therefore, there are 12 chord families.

Yes, there’s an entire chord family for each note.

The notes are A, A#, B, C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, and G# and each has a unique chord family.

But let’s get a little more technical and go deeper into the topic.

The definition of a “chord family” is a group of chords that sounds well together naturally, as part of the same key.

Perhaps, keys and scales are concepts you’re familiar with. Well, they will be very handy in this article because the concept of chord family is very close to them.

Every degree of the scale or chord of the family will fulfill its role by expressing its chord quality; for example, being major, minor, or diminished.

Also, if all the chords in a given family belong to the same key, it means that they have a harmonic function that is dictated by their distance to the key they belong to.

I know harmonic function sounds very complex. Yet, this complicated term can be translated as how these chords handle tension and what emotional content they can convey.

For example, while some chords create tension and sadness, others resolve the tension by sounding triumphant, full, and happy.

Yes, the chords in a song tell a parallel story to the lyrics adding sweet, sour, sad, or happy elements to the mix.

You guessed it, by knowing the chord families you can use all these emotional elements in your favor as a songwriter and guitar player.

Also, it can be the perfect way to anticipate what kind of a chord will come next in a ballad, a pop song, a blues tune, or a reggae anthem.

Did all of this sound a little like mumbo jumbo?

Don’t worry about it; we’re going deep into explaining every concept with the best ten tips you need to master every aspect of chord families, fast.

The Who’s Who of the Chords in the Family

In every family, each sibling is different. Likewise, in chord families, every chord has its own “personality”.

Moreover, the similarities with real life don’t end there. Every chord in the family has got a duty to fulfill and brings a unique element to the mix.

For example, while the super tonic could be pushing the song in one direction, the dominant could enter the scene and bring enough tension to make it impossible not to resolve it by playing the tonic.

This role interchange is paramount to telling the story of the song. Also, it is a great help in finding the story in each song we play.

We’re going to learn several layers in the personality of each of these chords, so let’s do it.

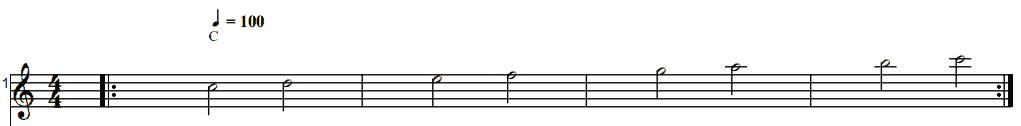

Meet “The C Family”, our Example

This family of chords has seven elements. It is what we call a natural scale because it doesn’t have any flats or sharps.

The C family looks like this:

I – II – III – IV – V – VI – VII – I

C – D – E – F – G – A – B – C

This is the family of notes, but we need to turn this into a family of chords, so we’ll see two ways of doing that. The first will give us as a result the C major chord family and the other one will give us the A minor chord family.

Both share the same chords but are arranged differently, around a different tonic. As I said above, there are 12 families, but the chords that make these families can be arranged in more than one way creating different textures.

We’ll start with major and minor and, as a bonus track, I’ll share with you a very handy chart to find the relative minor to every major family.

More on that later, let’s talk about the C major example.

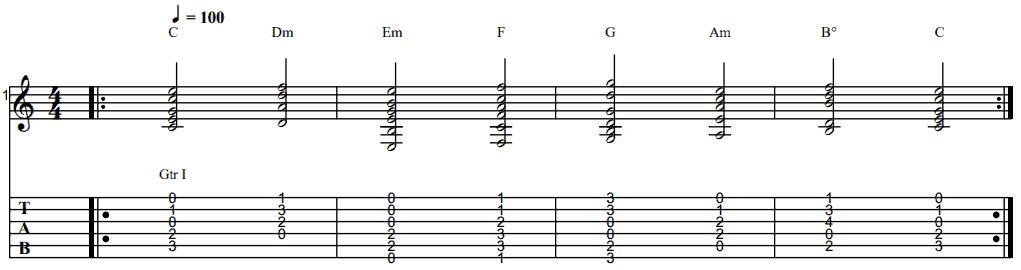

The C Major Chord Family

Let’s make a little pause; I have to give you a small caveat about something I’ve heard many times among colleagues. The fact that a scale, key, or family is major or minor, doesn’t mean every chord in it is major or minor.

So, in the C major chord family, we will find major, minor, and diminished chords. These are laid out in a given order, they follow a formula; it goes like this:

- I – Major

- II – Minor

- III – Minor

- IV – Major

- V – Major

- VI – Minor

- VII – Diminished

So, if we put this into the C major family, we’ll obtain the following chords.

- C Major

- D Minor

- E Minor

- F Major

- G Major

- A Minor

- B Diminished

This formula: major, minor, minor, major, major, minor, diminished repeats in every major chord family. So, as long as you know what key, family, or formula the song is in, you’ll be able to know what chord choices you have.

For example, if you’re trying to play someone else’s song and you know it’s in the C major key, you know you’ll find E and A being minor and F and G being major. Also, you won’t likely come across an F# or a D# chord.

There are exceptions, of course, music is all about breaking the rules, but this idea will cover a vast sonic territory.

Furthermore, as we said before, it isn’t that everybody plans their music mathematically to create a hit that sounds good. These phenomena already occur in music; we’re just creating a shortcut and naming it.

So, next time you’re composing your material, you’ll know that if you’re in the key of C major, you shouldn’t go for A major but for A minor.

And you know what? It will sound better too.

You can think of the chord family as a catalog to choose your chords from. If it’s on the list, it’ll sound good.

Here’s a chart of every major chord family for you to have and check as many times as you want.

| Key | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII |

| C Major | C Major | D minor | E minor | F Major | G Major | A minor | B diminished |

| Db Major | Db Major | Eb minor | F minor | Gb Major | Ab Major | Bb minor | C diminished |

| D Major | D Major | E minor | F# minor | G Major | A Major | B minor | C# diminished |

| Eb Major | Eb Major | F minor | G minor | Ab Major | Bb Major | C minor | D diminished |

| E Major | E Major | F# minor | G# minor | A Major | B Major | C# minor | D# diminished |

| F Major | F Major | G minor | A minor | Bb Major | C Major | D minor | E diminished |

| F# Major | F# Major | G# minor | A# minor | B Major | C# Major | D# minor | F diminished |

| G Major | G Major | A minor | B minor | C Major | D Major | E minor | F# diminished |

| Ab Major | Ab Major | Bb minor | C minor | Db Major | Eb Major | F minor | G diminished |

| A Major | A Major | B minor | C# minor | D Major | E Major | F# minor | G# diminished |

| Bb Major | Bb Major | C minor | D minor | Eb Major | F Major | G minor | A diminished |

| B Major | B Major | C# minor | D# minor | E Major | F# Major | G# minor | A# diminished |

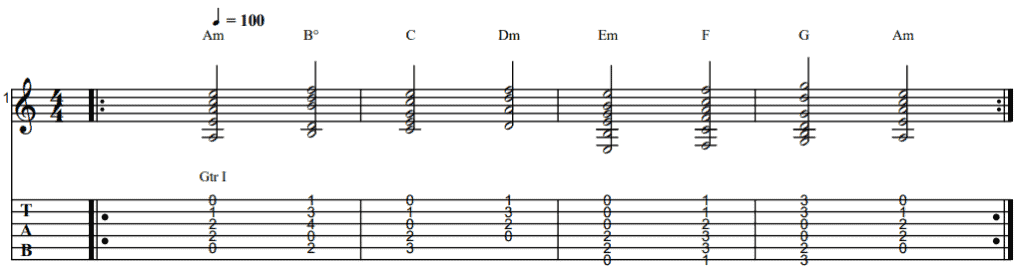

The A Minor Chord Family

Although minor chord families are different from major chord families, they behave exactly the same. This means that even though intervals change, they act as the same catalog of chords you can choose from for your songwriting efforts or when trying to make out other people’s tunes.

Moreover, you’ll soon realize, though, that, although intervals change, the chords are the same but built around a different tonic (or I chord). Don’t worry if it sounds a little strange now, you’ll grasp the concept perfectly when we get to the chart.

So, the structure to put together every minor family looks something like this:

- I – Minor

- II – Diminished

- III – Major

- IV – Minor

- V – Minor

- VI – Major

- VII – Major

The relative minor key, scale, or family to C major is A minor. Let’s see what the A minor scale, key, or family looks like:

- A Minor

- B Diminished

- C Major

- D Minor

- E Minor

- F Major

- G Major

Yes, if you start your C major scale from degree V, which is A minor, you’ll get all the same chords but in a different order.

Let’s see a minor families chart:

| Key | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII |

| A minor | A minor | B diminished | C Major | D minor | E minor | F Major | G Major |

| Bb minor | Bb minor | C diminished | Db Major | Eb minor | F minor | Gb Major | Ab Major |

| B minor | B minor | C# diminished | D Major | E minor | F# minor | G Major | A Major |

| C minor | C minor | D diminished | Eb Major | F minor | G minor | Ab Major | Bb Major |

| C# minor | C# minor | D# diminished | E Major | F# minor | G# minor | A Major | B Major |

| D minor | D minor | E diminished | F Major | G minor | A minor | Bb Major | C Major |

| Eb minor | Eb minor | F diminished | F# Major | G# minor | A# minor | B Major | C# Major |

| E minor | E minor | F# diminished | G Major | A minor | B minor | C Major | D Major |

| F minor | F minor | G diminished | Ab Major | Bb minor | C minor | Db Major | Eb Major |

| F# minor | F# minor | G# diminished | A Major | B minor | C# minor | D Major | E Major |

| G minor | G minor | A diminished | Bb Major | C minor | D minor | Eb Major | F Major |

| G# minor | G# minor | A# diminished | B Major | C# minor | D# minor | E Major | F# Major |

Bear in mind that there’s a relative minor key for every major key; in other words, every major family has a relative minor family that has the same chords arranged around a different tonic.

In this case, we did it with the only two families with no sharps or flats (C major and A minor) to make it easier to explain. So, if you encounter an A and E minor chords in what you’re playing you might be in the A minor or C major families.

This is a concept that many people refer to as “The Circle of Fifths”. You might have heard it or seen it before somewhere.

Now, this is my gift to you, the bonus track. Using this chart, you’ll be able to navigate from major to minor easily.

| Major Key | Relative Minor Key |

| C Major | A minor |

| D Major | B minor |

| E Major | C# minor |

| F Major | D minor |

| G Major | E minor |

| A Major | F# minor |

| B Major | G# minor |

| Db Major | Bb minor |

| Eb Major | C minor |

| Gb Major | Eb minor |

| Ab Major | F minor |

| Bb Major | G minor |

Chords, Emotions, Families, and beyond

Now that you are familiar with major and minor families and their chords, we have to talk about what each of the chords in these families can do.

To begin with, as a rule of thumb, minor chords are sad and dark while major chords are happy. Also, minor chords generate tension that the major chords try to resolve.

Finally, there’s a special relationship between the V and VII degrees and the I degree. Yes, while the first two beg for resolution, the I chord is the embodiment of resolution itself.

So, if we apply this information, what we get for the major scale is:

- Degrees I, IV, and V are major.

- Degrees II, III, and VI are minor

- Degree VII is diminished.

In the minor scale, it works like this:

- Degrees I, IV, and V are minor.

- Degrees III, VI, and VII are major

- Degree II is diminished

So, for example, if you’re working on the sad verse of a song (yours or not), you should try with minor chords or the minor family. On the opposite, if everything sounds happy, huge, and colorful, you can try with major chords or the major family.

What I’m trying to say is that these chords and chord families convey distinct emotions. By knowing which chord does what, you can always be one step ahead and use the tension management and emotional quality of these chords to their maximum.

Chord Families, Degree per Degree

Let’s talk about each of the degrees in the family and what it does to maintain family harmony.

First, let’s take a look at the next layer in these chords’ personalities and their names. The chords in a scale, key, or family look something like this:

- I – Tonic

- II – Super tonic

- III – Mediant

- IV – Sub-dominant

- V – Dominant

- VI – Sub-Mediant

- VII – Leading Tone

Tonic (I)

The tonic is the note or chord that gives the family its name. Also, it is the chord to which everything can resolve.

In this sense, we can say that tension rising in most compositions can be solved by playing the tonic. Yes, the triumphant entrance of the root note feels a lot like “going home” or resolving the tension.

For example, if you’re playing with the family of C major, you can always resolve to the C and find a feeling of comfort when you play it. This will not only happen to you, but also to whoever is listening.

So, in a nutshell, the almighty tonic is great to put a smile on the face of listeners, make a big statement, and solve the tension.

Plus, the tonic will dictate what family we’re in, and therefore, what chords we’ll use.

Super Tonic (II)

The first chord we find after the tonic is called the super tonic. This chord will be minor in major families and diminished in minor families.

The main thing you have to know about the Super Tonic chord is that it is a tension raiser that goes very well with the Dominant (V) degree (don’t worry, we’ll see more about that chord later).

So, it is not uncommon that this chord is used as a pivotal chord to go to the V degree. For example, we can see this in several famous chord progressions:

- II – V – I – IV – This chord progression can be heard in: “Still got the Blues” by Gary Moore, “Europa” by Santana, and “I Will Survive” by Gloria Gaynor.

- I – V – II – V – This chord progression can be heard in: “Perfect” by Ed Sheeran, “Jesus of Suburbia” by Green Day, and “Every Breath you Take” by The Police.

As you can see, in both examples, the II chord is always resolving to the V chord, and then, very likely, to the tonic.

Mediant (III)

Mediant in Latin means middle, and that is exactly what this chord represents. This chord is minor in major families and major in minor families.

But what’s the particularity of the mediant chord? Well, just like chord II is always pushing you to play the V chord, the III will always want you to go to the IV chord.

So, in a way, you can think of this chord as a passing-by note that builds up the tension leading to the sub-dominant. Moreover, if you let all these chords accumulate tension (moving from III to IV and from IV to V), the audience, the song, and you will be begging for resolution by the time you reach your tonic or I.

That being said, the III chord is among the least used in Western music, so if you want to be authentic and original, try to mix it in your compositions.

Sub-Dominant (IV)

The sub-dominant chord is directly below the dominant, and it acts mostly as a dominant preparation chord. In other words, we can say that every time we play chord IV, we’re raising the tension of the composition.

Also, in a major family, it is the second major chord we can play, which makes it a perfect way of leveling up the tension in the piece without changing its mood or feeling. Likewise, this chord becomes minor in minor families keeping the vibe intact.

Yes, if you were playing either of the minor chord we saw before (II and III), you can go to the IV chord to get the tension up one more notch, as you prepare for the resolution.

Dominant (V)

The dominant is the V degree and is, by far, the biggest tension-raiser in the family. Yes, every time we play the dominant, we feel there’s a certain urgency to go running to our tonic or degree I.

This is something you’ve heard a million times in your life in a plethora of families, keys, or scales.

For example, (besides the 12-bar blues) songs like these have made it to stardom utilizing the I-IV-V-I progression:

- “Like a Rolling Stone” by Bob Dylan

- “Born to Run” by Bruce Springsteen

- “Rock and Roll All Nite” by Kiss

- “Mr. Jones” by Simon and Garfunkel

- “Twist and Shout” by The Beatles

- “La Bamba” by Ritchie Valens

And the list could go on forever, but you get the idea of just how important the tandem V – I has been to the history of popular Western music.

PRO TIP

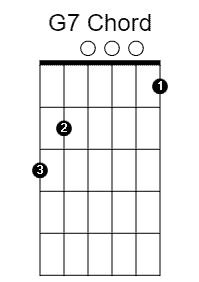

As a pro tip, let me tell you that if you transform the dominant chord to its seventh version (you add a fourth note), you’ll duplicate the sense of urgency to resolve to I. You can try it right now: grab your guitar and play C, F, G, and C and C, F, G7, and C.

You’ll realize in a second that the second version becomes more dramatic. In case you don’t know the G7 chord, you can play it like this:

Sub-Mediant (VI)

The Sub-Mediant chord is a chord that can generate some kind of deceit in the listener.

How so, you might be wondering?

Well, if you play something like IV – V – VI, this last chord will want you to resolve to IV instead of resolving to I. Once you go back to IV, you can play the V and go back to the tonic.

For example:

- I – V – VI – IV – “With or without you” by U2, “When I come around” by Green Day, “Bullet with butterfly wings” by the Smashing Pumpkins, “It’s my life” by Bon Jovi, and “Otherside” by the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

- VI – IV – I – V – “Electrical Storm” by U2, “Little Talks” by Of Monsters and Men, “Numb” by Linkin Park, “Snow (Hey Oh)” by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and “The Kids Aren’t Alright” by The Offspring.

As we can see in these two examples, the resolution of VI is almost always IV. In the case of our C major family, we could say that chord VI (Am) will always sound great going to chord IV (F).

Leading Tone (VII)

The leading tone is the VII degree of the family or scale and is, at least for major scales, a diminished chord. These chords are built utilizing minor thirds, which gives them a somber, odd, different tone.

Although you won’t come across diminished chords all that often in contemporary Western music (even less in simple pop structures), they are very useful to throw in a different flavor to the mix.

The name “leading tone” comes from the fact that this chord is great as a transition to go to the I degree of the family. Therefore, it’s the tone leading to the tonic.

PRO TIP

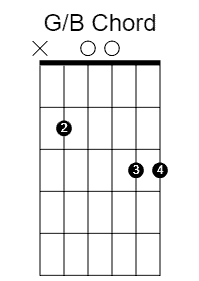

As a pro tip, a common trick we all do with this chord is to add its root note to the dominant chord (V). In the case of the C major scale, for example, that would be to add a low B to the G chord.

By doing that, you’ll create a slash chord (a chord in which the lowest note is not the root or tonic) that will beg to resolve to the I degree (C).

This chord looks something like this:

Chord Families & Modes

We said before that there are several layers in the personality of the members of these chord families. We already saw the chord quality (major, minor, and diminished) and the harmonic function (tonic, supertonic, and such).

Well, the major and the minor are just two of the many families or keys you can play on your guitar. Indeed, what happens if we apply the same principle of note arrangement to each of the seven modes in guitar?

Yes, we get even more chord families.

Within each of these new families, the chords will respect their harmonic function. Also, each of the modes will have major, minor, and diminished chords.

Why is this important you might be asking me, yourself, and the universe?

Well, very simply, if you know that you’re playing in C Ionian, for example, you know the song will have D, A, and E minor while F, G, and C will be major.

Not bad, uh?

Well, let’s go mode by mode so you can acquire this new, powerful knowledge:

Ionian Mode

The Ionian mode is the same as the major scale. This means that everything you just saw about the Major scale applies to this first mode.

The only difference here is that we will use the intervals to define the scale or mode. The Ionian mode is formed utilizing the following intervals

F= Full tone (2 frets on the guitar)

H= Half tone (1 fret on the guitar)

F – F – H – F – F – F – H

So if we were to use again our C major scale, or C Ionian, we would have the following chords:

- C major

- D minor

- E minor

- F major

- G major

- A minor

- B diminished

If we strip down the chord names, what we’ll get is:

- I Major

- II Minor

- III Minor

- IV Major

- V Major

- VI Minor

- VII Diminished

Dorian Mode

While the Ionian mode is major, the Dorian Mode is minor. To obtain the Dorian mode with no sharp or flats, you have to move the same structure we talked about above one tone toward the next note in line: D.

So, to our previous example of C Ionian, we’ll add the D Dorian.

The formula for this mode is slightly different from the previous one; it goes like this:

F – H – F – F – F – H – F

Instead of using our C major scale, or C Ionian, we’re going to see our D Dorian family chords:

- D minor

- E minor

- F major

- G major

- A minor

- B diminished

- C major

If we strip down the chord names, what we’ll get is:

- I Minor

- II Minor

- III Major

- IV Major

- V Minor

- VI Diminished

- VII Major

Phrygian Mode

Another minor mode, the Phrygian mode, can be created by moving the Dorian mode up one note. If we were to use it to create the C Phrygian family, it would give us something like C, Db, Eb, F, G, Ab, Bb, and C.

We’re going to strip it to the intervals:

H – F – F – F – H – F – F

To demonstrate the chords of the Phrygian mode, we’ll use E Phrygian, which will give us a family with no sharps or flats.

- E minor

- F major

- G major

- A minor

- B diminished

- C major

- D minor

If we strip down the chord names, what we’ll get is:

- I Minor

- II Major

- III Major

- IV Minor

- V Diminished

- VI Major

- VII Minor

Lydian Mode

After going through two minor modes, Lydian is another major mode that sounds full and round. When applied to the C scale, we can form C Lydian which would be C, D, E, F#, G, A, B, C.

The intervals in this mode are:

F – F – F – H – F – F – H

These are the chords we get when we apply these intervals to the perfect Lydian mode (no sharps or flats), which is F Lydian.

- F major

- G major

- A minor

- B diminished

- C major

- D minor

- E minor

If we strip down the chord names, what we’ll get is:

- I Major

- II Major

- III Minor

- IV Diminished

- V Major

- VI Minor

- VII Minor

Mixolydian Mode

This major mode is the fifth mode and if applied to the C family or scale would give us C, D, E, F, G, A, Bb, C. This formula, if stripped down to the distances between the components looks like this:

F – F – H – F – F – H – F

The perfect scale or family to explain the Mixolydian mode chords is G Mixolydian. It looks like this:

- G major

- A minor

- B diminished

- C major

- D minor

- E minor

- F major

If we strip down the chord names, what we’ll get is:

- I Major

- II Minor

- III Diminished

- IV Major

- V Minor

- VI Minor

- VII Major

Aeolian Mode

The Aeolian mode is a minor mode that is exactly the same as the minor scale we saw above. Every single rule that applies to the minor scale applies to the Aeolian Mode. If we were to apply it to the C scale or family, we would get C, D, Eb, F, G, Ab, Bb, C.

That formula without notes looks like this:

F – H – F – F – H – F – F

The relative scale to C major is A minor. Therefore, the best way to show the chords with no sharps or flats is using A Aeolian.

- A minor

- B diminished

- C major

- D minor

- E minor

- F major

- G major

If we strip down the chord names, what we’ll get is:

- I Minor

- II Diminished

- III Major

- IV Minor

- V Minor

- VI Major

- VII Major

Locrian Mode

The Locrian Mode is always special since its first degree is diminished. This is not just a minor detail; it gives the entire mode a particular mood, color, and emotional content.

That being said, if we were to apply it to our C scale, we’d get C, Db, Eb, F, Gb, Ab, Bb, C.

Stripping down the chords, we get the following formula:

H – F – F – H – F – F – F

The best way to display the chords that make the Locrian Mode family is using B Locrian.

- B diminished

- C major

- D minor

- E minor

- F major

- G major

- A minor

If we strip down the chord names, what we’ll get is:

- I Diminished

- II Major

- IIi Minor

- IV Minor

- V Major

- VI Major

- VII Minor

What are the most common chord families?

This is a very important question, especially for guitar players like us. Yes, we have something other disciplines don’t have that makes our lives easier.

I’m talking about the almighty CAGED system.

The CAGED system is something that a violin player will never find for his or her instrument. It works like a shortcut that can accelerate your learning process by maximizing ROI.

Hey, what is ROI? Return On Investment means you get more bang for the buck; in other words, you make a small effort and cover vast sonic ground.

Wait, I might be going too fast; do you know what the CAGED system is?

Well, in case you don’t know, it’s a system of notes and chords that will help you navigate the entire fretboard with five families.

CAGED, it’s an acronym that stands for the chord families C, A, G, E, and D.

These are what we know as open-position chords. Utilizing their shapes, we can come up with any chord we want in the entire fretboard.

Likewise, using the notes in the scales or families of the CAGED system, we can map out the fretboard covering every position.

Therefore, the most famous and important chord families you have to learn are the ones that belong to the CAGED system.

Let’s refresh each key of the CAGED system in major and minor:

| Key | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII |

| C Major | C Major | D minor | E minor | F Major | G Major | A minor | B diminished |

| A Major | A Major | B minor | C# minor | D Major | E Major | F# minor | G# diminished |

| G Major | G Major | A minor | B minor | C Major | D Major | E minor | F# diminished |

| E Major | E Major | F# minor | G# minor | A Major | B Major | C# minor | D# diminished |

| D Major | D Major | E minor | F# minor | G Major | A Major | B minor | C# diminished |

| Key | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII |

| C minor | C minor | D diminished | Eb Major | F minor | G minor | Ab Major | Bb Major |

| A minor | A minor | B diminished | C Major | D minor | E minor | F Major | G Major |

| G minor | G minor | A diminished | Bb Major | C minor | D minor | Eb Major | F Major |

| E minor | E minor | F# diminished | G Major | A minor | B minor | C Major | D Major |

| D minor | D minor | E diminished | F Major | G minor | A minor | Bb Major | C Major |

10 tips for learning chord families quickly on the guitar

OK, we’ve gotten to the moment you have been waiting for: the tips to learn all of this faster and make it part of your playing.

I made a titanic effort and somehow managed to condense two decades and a half of playing in only 10 tips. So, use them thoroughly and let this chord family superpower take over your playing to make you a better guitarist.

1. Information Chunking

According to Cognitive Psychology, chunking information helps our working memory bypass its limited capacity and store more information better. A plethora of studies, like this one, confirm this theory.

But how does information chunking work? It’s very simple, you have to find a common quality and put information in that group.

So, if we were to apply information chunking to chord families, what we should do is learn, for example, the intervals that make one of the modes.

So, let’s say that you take the Ionian mode intervals:

F – F – H – F – F – F – H

Now apply it to every family of the Ionian mode in the CAGED system.

- C Ionian

- A Ionian

- G Ionian

- E Ionian

- D Ionian

With this chunking method, your memory will be associating this information and storing it faster. Plus, next time you want to bring one of these families to your mind, you’ll also be able to recall it faster since it’s stored in a chunk.

Moreover, by the time you’re done with the chunking of the first key or family, you can move on to the second and so on until you’ve memorized them all in less time than without chunking the info.

Finally, you’ll surely realize that you can recall more chord families than you thought you could by utilizing this technique.

2. Start with the CAGED system

The second tip to learn this information quicker is one I wish I was given when I was learning chord families a long time ago. If you can learn the chord families contained within the CAGED system, you’ll be covering at least 70% of your playing if you like contemporary Western music.

This means that you can do an effort to sink in all the information in these five families and play a plethora of songs or create a lot of music.

So, above you have the major and minor family of each of the CAGED system root notes. Start with them until you can play them back and forth by heart.

Once you’re done with them, move on to the rest of the families with the certainty that you can handle the most-used chord families in Western contemporary music.

3. Work one family at a time

Biting off more than you can chew is a common problem among guitar players. Yes, very often we find ourselves overtaken by anxiety and trying to learn everything overnight to be a killer guitar player by tomorrow morning.

Well, I’m sorry to be the one that carries the bad news, but you have to practice a lot to become a great guitar player. That won’t happen overnight, over-week, or even over-month.

That being said, you can learn all chord families and become the guitarist you always dreamed of. It’s just that you have to learn and practice one at a time.

For example, if you are to start with the CAGED system, the perfect way of doing it is to start with the C family (major and minor). Once you know it inside out by heart and you can play it in any combination entirely, you are ready to move on to the A family.

When you’re done with the C and the A, you can move on to the G and so on until you cover all the information you want or need.

Remember, don’t let anxiety win you over, learn one at a time and let the information sink in before moving on.

4. Play every family at least 8 to 10 times a day

Speaking of information sinking in, once you learn each of the families, practice them at least 10 times every day.

Why this obnoxious amount of repetition, you might ask? Well, unless you use them and practice with them, chord families will be no different than the muscles of the hand, or the stars in the galaxy: pieces of impossible-to-remember information.

Once you play each of them at least 10 times a day, you’ll grasp the nuances and give your brain sounds to associate this data with.

As a result, you’ll very likely be able to bring this information up in the situations you need it. For example, high-stress scenarios like the stage of a jam, a studio session, or when songwriting or learning other people’s songs.

5. List down three songs to learn per family

I’m not going to be that annoying teacher that makes you learn a lot of theoretical stuff and gives you no fun exercises to work with.

So, if you want to practice each family ten times, why not learn some tunes that go with the family and play those instead of just the chords?

Let’s start this tip together. Let me give you three iconic songs written in C major and C minor and you can fill in the rest.

C Major songs:

- “Imagine” by John Lennon

- “Use Somebody” by Kings of Leon

- “Another Brick in the Wall” by Pink Floyd

C Minor songs:

- “Come together” by The Beatles

- “It’s my life” by Bon Jovi

- “We are the champions” by Queen

Repeat this same idea for the rest of the families or keys and have some fun while memorizing something new.

6. Break the chords down into notes

This is another interesting way to work your memory. This is something that I couldn’t do until I got much deeper into guitar playing.

Yet, the first time my brain did it on its own, it was like a whole new universe opening up for me. It was like that scene of The Matrix when Neo finally sees the Matrix in everything.

I could swear I heard the same holy music sounding in the background in my head too!

But the important thing is that, once you start seeing the notes that make the chords, you’ll be able to break down the theory several steps further. For example, if you break down the CAGED system chords into the notes that form them, you can use these shapes to create melodies, riffs, and arrangements.

Let’s break this into two parts.

For part one, you have to note down the notes that make every chord in the family. This will look something like this:

- C Major Chord: C – G – E

- D Minor Chord: D – A – F

- E Minor Chord: E – B – G

- F Major Chord: F – A – C

- G Major Chord: G – B – D

- A Minor Chord: A – C – E

- B Diminished Chord: B – D – F

As a second step, you have to find these notes in the first five frets of the guitar and try to find new ways to create these chords. Before you know it, you’ll master the CAGED system in ways you never even imagined.

Furthermore, once you see the Matrix on your fretboard, you’ll be one step closer to becoming a proficient musician who can play on the stage of any jam and can create amazing new music for the world to enjoy.

7. Break the 20-time limit

Your brain decides what information to store and what to forget. Can you imagine if we could remember every little piece of inane conversation ever had?

Yes, we would live in a sea made of words that resemble plastic and garbage.

Well, the human body is more perfect than that, but we need to show it the way. Yes, your brain reads the repetition of a certain activity as an indicator of its importance to survival.

We’re talking biology here, so these mechanisms are hundreds of thousands or even millions of years old.

That being said, in this day and age of humankind, instead of perfecting our aiming throwing a spear to get to the jugular of a tiger by repetition, we’re going to practice the chords in a given family.

Now, let’s take this concept a little further.

Every time you break the 20-time limit (AKA, you play it over 20 times) with whatever you’re practicing, you’ll engage this archaic mechanism and tell your brain to store that information.

Therefore, if you want to tell your brain what to do with this information you’re feeding it, make sure you repeat the same chord family at least 20 times so it will know what to do with it.

Here’s more on this topic of practice and remembrance in case you want to investigate further.

8. Repeat – SPACE – repeat – SPACE – repeat – SPACE – repeat

Have you ever heard about the “spacing effect”? Perhaps you’ve heard the terms “spaced repetition” or “spaced-out studying”?

Well, if you haven’t, it’s about time you do because it’s of a great deal of help when trying to memorize something quickly.

The rule is that repeating something 10 times in the lapse of a week is more effective than doing it 50 times in a day.

This is because our new neural connections need time to solidify before we can put any new information on top of them.

If you want to make a comparison, think of it as building a house; you can’t put the roof if the cement between your bricks is still fresh.

Just like in the example of the analogy, if we give our brain the possibility of solidifying knowledge, there’s a greater chance we learn that information more thoroughly, and thus, faster.

In case you’re wondering, I feel truly flattered, but this is not an idea that occurred to me; it belongs to a scientist named Pierce J. Howard. He wrote a book about it called “The Owner’s Manual for the Brain: The Ultimate Guide to Peak Mental Performance at All Ages”.

So, if we apply this to chord families, we can say that a good approach would be learning the C, and going back to it every day of the week while you’re learning the other four families. Hopefully, by Friday the C family of chords will be solidified and waiting for you to use it at any time.

I assure you, information will be solid as a rock following this criterion.

9. Sleep on it

Just like in the previous step, it’s not me making this affirmation. In this case, is no other than the prestigious Harvard University.

Yes, the role of healthy sleep in the acquisition of knowledge is something that has been studied a lot in humans. The conclusion of the Medical Department of the University of Harvard is that sleep not only helps solidify knowledge the night after we acquire it but is paramount the night before too.

In other words, sleeping well before and sleeping well after acquiring knowledge is very important to enhance our body’s capacity of taking this information and letting it sink in faster.

So, start with the C family, sleep over it, and then start with the A family. If you start on a Monday, by Friday, all families will be solid in your memory.

10. Consistency playing them

Finally, there’s no other way of solidifying information that’s faster than using it consistently. Yes, it is worthless to go all-in with these tips for a week and then stop.

So, let’s put this information to use through a very simple exercise that will cover the most famous chord progressions in history.

The idea is that you fill in the chords in these empty structures and then play them. You can get started with the CAGED families and then move on to the rest of them.

I’m going to note down the progressions here with only the degrees. You have to fill in the chords using the information in this post for every chord family and then play them to hear the result:

- I – IV – V – I – The most famous progression of all time

- VI – I – V – II – Let the arena sing along with you

- I – V – VI – IV – Adding emotion to the mix

- VI – IV – I – V – Mainstream hit-maker

- II – V – I – IV – Guitar heroes’ secret sauce

- I – bVII – IV – V – Don’t be afraid to be odd (and use a flat seven!)

- I – V – II – V – The incomplete cadence (or half cadence)

By the time you have filled each of these chord progressions with the chords of each of the families, you will have a much clearer memory of them and also, as a welcome side effect, will be able to play a plethora of new songs.

Not bad, uh?

The Bottom End

Although it is not such a simple concept theoretically, learning chord families has a plethora of benefits for every player.

That being said, once you start putting this information to work, you’ll realize it is rather simple to use and it opens many doors.

Yes, chord families are crucial for anyone serious about guitar playing. Furthermore, regardless if you love to jam with friends, play other people’s songs, or create your own; this skill will signify a major step forward in your career.

So, practice, practice, and practice some more following our ten tips and be a better guitarist by next week.

It’s not magic, but by the time you dominate chord families, it will surely feel like it.

Happy playing!

Hello there, my name is Ramiro and I’ve been playing guitar for almost 20 years. I’m obsessed with everything gear-related and I thought it might be worth sharing it. From guitars, pedals, amps, and synths to studio gear and production tips, I hope you find what I post here useful, and I’ll try my best to keep it entertaining also.