Probably when you first thought about playing the guitar the idea came to you because of how fun and cool it looks.

Shredding in front of an audience or just being able to play a song for others to sing along is a beautiful feeling.

However, at some point, you might have found out that it is not all amusement.

This tends to happen usually when players find out that there’s a lot of music theory out there that they would benefit from learning.

Key takeaways:

- There are 12 different musical notes despite some sharing their letter name and being modified by either the term “flat” or “sharp”

- Every musical note is a semi-tone apart from the ones next to it

- Flats and sharps have nothing to do with minor or major chords

- Melody means pitches with rhythm

- Harmony is the science of making things sound nice together

- Music is divided into bars and notes have standardized durations

- Intervals refer to the distance between 2 particular notes

- Chords are groups of notes that sound nice when played together

- Chords have different qualities or types that evoke certain feelings

- Scales are lists of notes that sound well together

- By combining the notes on a scale you can find chords within it

- Every scale has its particular modes that share the same notes but shifts their order

- There’s a lot more to music theory than this but I recommend you focus on the basics and then move to ear training and improvisation

In this article, I will try to condense briefly all the main topics about music theory that any guitarist would find useful when starting out.

After leaving this page, you will have a clearer idea of how to focus your theory-learning effort, and maybe have a better grasp of the most important concepts of formal music learning.

Are you ready to get started?

Let’s go!

Disclaimer: I will simplify things a lot here, and by doing so the way I lay out some concepts might not pass the strictest revisions by professional musicians. I encourage you to not take anything you read here as absolutely certain, but only as a friendly encouragement to dive deeper (and more academically) into the topics that you think might help your art.

Guitar theory vs music theory

I’ve got good news for you:

There’s no such thing as “guitar theory”.

No, really. Music is just music, and when you learn it you will see it works out for every instrument.

At least western music theory, which is what I think most of my readers grew up listening to, and what rules most instruments that came from European roots.

The idea of guitar theory is just a way of visualizing musical concepts on the guitar fretboard.

No more than that.

But rest assured that if you learn today how to build a chord, and can name its notes, you will also be able to play that chord on a piano, once someone tells you where those notes are.

Basic concepts and terms

There are probably hundreds of concepts and terms that are unique to music, however, here are a few of the most basic ones you should understand.

There are 12 musical notes

I remember how when I didn’t know anything about music got this all wrong.

There are 12 musical notes, because of physics and math reasons that I will not butcher today, but I encourage you to Google or YouTube.

These notes are:

| A | A# | B | C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# |

A common misconception is thinking that for instance A# (A sharp) is not an individual note, but something that’s deeply connected with A.

I would argue that its only connection is being close together.

By all means, A# could have been named Richard and nothing would change other than saving us from these confusions.

Tones and semi-tones

Each note is a semi-tone apart from the next one in the list above.

But also you can think about this list as a circle because if you go up a semi-tone from G# you will find a new instance of A, only that this time it sounds higher in pitch.

The list repeats itself in what’s called an “octave” higher, but the notes are the same.

The “height” of the notes is usually represented by their position on a musical pentagram, or just by what fret a guitar TAB indicates you should play.

Going a semitone below the first A of the list you will find a lower G# and what I said above for going upwards works as well for going downwards.

A tone is 2 semitones.

So, from A to B you have a distance of a tone.

Now, if you go up a tone from B you will get to C#.

And so on.

Sharps and flats

There are 2 ways of thinking about these notes that have a symbol on their side.

You can either think of them as the sharp version of the one preceding them, or the flat version of the one in front of them.

A list of the 12 notes with flats looks like this:

| A | Bb | B | C | Db | D | Eb | E | F | Gb | G | Ab |

You will see how particularly G# is now Ab because it’s the note that you will find if you went a semitone up.

But why this confusion of having some notes with 2 different names?

Well, how you name them depends on the context.

We will introduce later the concept of musical scales where this will make sense.

Trust me.

Minor and major

Minor and major are terms usually associated with chords and scales.

There are no minor or major single notes.

People usually confuse this with sharps and flats, but these are completely different things that you will understand later.

As a tease: Minor musical “things” tend to sound sad while Major “things” sound happy.

Melody

A melody is a series of pitches (or notes) that have a rhythm attached to them.

You could sing the correct notes to the “happy birthday” tune, however, if you time them wrong, nobody would know what you are celebrating.

The same would happen if you just tap the correct rhythm on your desk.

Harmony

I consider harmony as the science of making things sound good together.

It’s a set of rules that lets us know what musical devices will work out just fine without the need of making any noise to listen to them.

On another level, you will usually hear musicians referring to “harmony” as the music that supports a melody.

Think of a songwriter strumming a guitar and singing: The strums are his harmony and the singing is his melody.

However, if you step out and see the whole picture, harmony also encompasses that melody.

But don’t get too deep about it, man.

Root and tonics

These are other 2 concepts that usually get thrown around interchangeably and everybody has an opinion about what they actually mean.

In my case, I usually refer as “root” to the note that gives a certain chord its name and “tonic” to the note that gives a scale its name.

These are concepts we will discuss later, but as another tease, the root of the first chord of a scale will be the scale’s tonic.

Rhythm

It is the foundation of music and probably the most primitive form of artistic expression.

You can’t have music without rhythm, and you probably have a preconceived idea about what it is.

I will now go into more specifics to make things clearer.

Beat vs rhythm

The beat of a song is a foundational piece of it that’s always present, and although it can change between parts is in most cases constant and acts as an ordering factor.

Beat can also be called pulse.

Rhythm, on the other hand, is what lies over that underlying beat.

Think about or put on a song that you link.

Now tap your feet to it.

You are tapping its beat.

But now, if with your hand you start tapping every note the singer sings, you would also be tapping the rhythm of the vocal melody.

Every instrumental or vocal part of a song has its particular rhythm that follows its beat, and that desirably works out nicely with what the other parts are playing.

Bars

They have the function of separating a piece of music into regular sections of a predefined duration.

However, bars are not a measure of actual time, but of beats.

Typically a bar has 4 beats or pulses, however, these beats can be closer or farther together.

Think of a ballad and a fast rock song.

They probably both are composed using 4 beats per bar, however, the ballad will make you tap your foot “slower” while the rock song will cause the opposite.

BPM

Or beats per minute is what defines how fast the beat to a song should be played.

By definition, it’s how many pulses at a given speed fit in a minute.

Musicians usually have references for this as it’s not humanly possible to play at a certain BPM by heart, however, it’s natural even for the untrained to lock into a certain beat at a given BPM.

Note durations

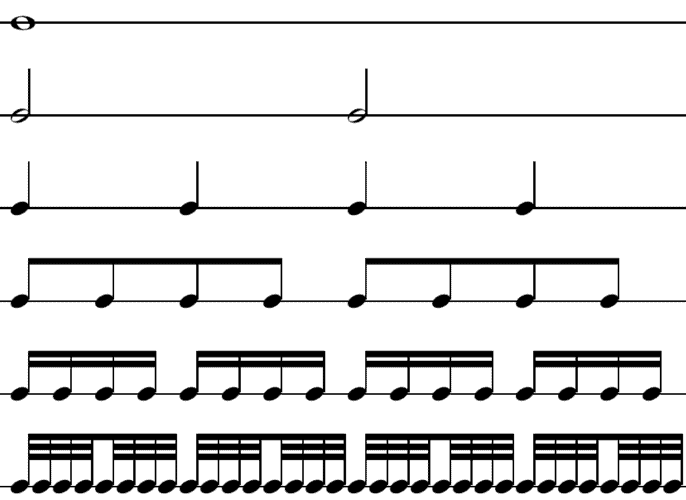

Musical notes have different durations as you can see in the following diagram of equivalences:

A whole note lasts for 4 beats, while a half note (the one in the second row) lasts for 2 beats each.

A quarter note lasts for a single beat.

When we go down we find that eight notes last for half a beat, and so on.

A bar of 4 pulses can be filled with any combination possible of these note durations, but no less, and no more.

Beats can also be subdivided into uneven groupings such as triples, quintuples, etc.

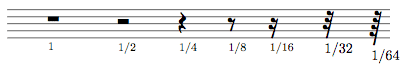

Rests

But what if there’s only a quick note sounding at the beginning of a bar and then silence?

Well, then you will have a bar with a sixteenth note, for instance, and the number of rests necessary to fill the rest of it.

Rests indicate silence for the amount (or fraction) of beats they correspond to.

Here are the figures used to represent them:

Time signature

I said that bars are made of usually 4 beats, but usually means “not always”.

You can actually define bars for every subdivision possible.

Time signatures are comprised of 2 numbers, the one below tells you a note duration and the one above how many of those notes will fit on a bar.

In 4/4 the time signature tells us that there are 4 quarter notes per bar.

In 6/8 there are 6 eight notes per bar.

Odd time signatures

Most western music is written in 4/4, 3/4, or 6/8, however, you can find lots of examples out there of weirder things such as 5/4, 7/8, 11/8, or 15/16, among many others.

Intervals

Intervals are specific distances between notes.

This is the distance in terms of harmony, but if you’d like to think about it in a more clear way, look at them as actual physical distance.

In a guitar, the bigger the interval between two notes is, the more frets there are between them.

In a piano, the bigger the interval, the more keys you find between those notes.

Knowing the exact relationship between two notes is important in music firstly to understand what sounds good with what, and secondly, to be able to communicate with other musicians.

Intervals are relative. You will see that a major third, for instance, is 4 semitones above a particular note, indifferent from which note we pick.

And this works for all other intervals too.

Most common intervals

The most common intervals you will find in the wild are probably the minor 3rd, the major 3rd, and the perfect 5th.

We will see a bit later how important these are for crafting chords.

All intervals

Now, here is a table of all intervals in music to make sense of them in context:

| Interval | Distance in semitones | Example note C |

| Unison | 0 (same note, same pitch) | C |

| Minor second | 1 | Db |

| Major second | 2 | D |

| Minor third | 3 | Eb |

| Major third | 4 | E |

| Perfect fourth | 5 | F |

| Tritone | 6 | F# / Gb |

| Perfect fifth | 7 | G |

| Minor sixth (or augmented fifth) | 8 | Ab (G#) |

| Major sixth | 9 | A |

| Minor seventh | 10 | Bb |

| Major seventh | 11 | B |

| Octave | 12 (same note, higher pitch) | C |

A good rule of thumb to learn them quicker is just to know that every interval has a minor and major variant, except for the fourth and fifth which are called “perfect”.

The tritone can sometimes be referred to as an augmented fourth or a diminished fifth.

Also, you will see that, for clarity, we don’t refer to the minor second as C# but as Db.

Each interval, when considered relative to a root note, is a different note.

There’s ambiguity for the augmented or diminished intervals, such as the tritone, or the minor sixth, that can also be thought of as an augmented fifth.

If this still doesn’t make any sense by now, don’t freak out. This is just a building block for later.

You don’t need to memorize the table above, there’s time to learn it.

Chords

Chords are probably the most important thing in music.

You probably know quite a few of them by now.

But learning how they work, and where they get their names from is important, again, to communicate with other musicians, and to understand what you are actually playing.

Building chords

There are some basic ground rules when building chords, and here is one of the first applications for the intervals we saw before.

- Chords have a root note that gives them their name: For example, for Am it’s A

- Chords can only have one of each “kind” of interval: Only one kind of third, only one kind of seventh, etc.

- Chords can’t have 3 consecutive intervals: You can’t have a major second and any kind of third (the one note is the first of the sequence here), you can’t have a fifth a sixth, and a seventh.

We will see later that these rules can somehow be broken.

Chord qualities

The quality of a chord is something that a lot of even intermediate players sometimes fail to understand.

On a higher level, what this quality defines is how that chord sounds.

Advanced players can clearly identify chord qualities out of the blue based on the emotion that they evoke in them.

Chords, in their basic form, are made of three notes: The root, a third, and a fifth.

We will quickly see an exception for this formula, though, with suspended chords.

The available chord qualities are the following:

- Minor

- Major

- Diminished

- Augmented

- Suspended

Now, referring back to intervals, here’s a table summarizing the intervals that comprise each of these chord qualities:

| Quality | Third | Fifth | Example with C |

| Minor | Minor third | Perfect fifth | C Eb G |

| Major | Major third | Perfect fifth | C E G |

| Diminished | Minor third | Tritone (diminished fifth) | C Eb Gb |

| Augmented | Major third | Augmented fifth | C E G# |

| Suspended second | No third, major second | Perfect | C D G |

| Suspended fourth | No third, perfect fourth | Perfect | C F G |

You can notice how for the different chord qualities of C (except for suspended) there always should be an E or a G, even if they are altered.

We never refer to a G# as an Ab within the context of a C chord.

Now, for suspended quality chords, know that the “suspension” that’s happening is for the third interval.

We suspend the third with either a major second or a perfect fourth.

This respects the ground rules for chords we defined earlier, since there are no three consecutive intervals.

And in terms of “feelings” let’s agree on the following:

- Minor chords sound sad

- Major chords sound happy

- Diminished chords sound dark and dissonant

- Augmented chords sound bright and dissonant

- Suspended chords (any kind) sound unresolved

Extensions

Extensions are spices you can add to your chords to get some extra flavor out of them.

The most basic extension possible (although in most books you will see them as part of the basic chord structure and not as an extension) are sevenths.

It’s pointless to discuss if we should call sevenths extensions or not at this level. Let’s say they just exist and can either be minor or major.

Now, higher extensions are when we start cheating and breaking the ground rules about chords I mentioned earlier.

See the following table:

| Interval | Interval + an octave |

| Minor second | Minor ninth |

| Major second | Major ninth |

| Perfect fourth | Eleventh |

| Minor sixth | Minor thirteenth |

| Major sixth | Major thirteenth |

As you can see, ninths, eleventh, and thirteenths are just the good old intervals we already met, but up an octave.

Them being an octave up allows us to wiggle out of the rule that doesn’t allow for a chord to be constructed with three consecutive intervals.

Let’s think of an example.

Say we want a C major chord that also incorporates a D.

D is the major second of C.

Now, if we build it like this: C D E G you will notice that C, D, and E are consecutive intervals of root, major second and major third.

Our way around this is either dropping the E and losing the major quality in favor of “suspending” the chord, or playing the D an octave up from the closest one to our C.

We will now have, ordered by pitch: C E G D which makes a C major ninth chord.

This is not the correct notation, but we’ll get there.

Inversions

Chord inversions sound way more difficult to understand than they actually are.

It just means to alter the order of pitches for the notes in a chord.

Basically, every 3-note chord, as the ones you surely know about has 2 inversions.

Let’s look again at a C major chord comprised of C E G.

At its root position, you are expected to play a C as its lowest note; this is why in guitar for the “cowboy chord” or open position you are intended to not play the low E string.

Now, if we go for the first inversion of C, in order of pitch we get E G C. We kicked the C an octave up, and now our “bass” note is the E.

The second inversion of our C major chord, as you would expect is G C E, now we pushed both the C and E an octave up.

Now the question is, do inversions really matter?

Well, excuse me academic musicians, but I’d say no.

They only matter if you are looking for a specific sound for a certain chord.

It is not technically wrong to play the “wrong” inversion of a chord since they are the same notes just arranged differently.

Of course, there are a ton of possible counter-arguments to this, but we are just talking about theory informally.

Chord notation

Chord notation is a pain in the butt, let me say.

This is perhaps the most complicated thing about the whole learning music thing.

Mainly because even within western music theory, there are different ways of notating the same things.

For instance, what you probably understand as an A minor chord, when notated as Am, you will see notated as an A- in jazz charts.

They are the same thing, just different ways of writing it down.

But apart from inconsistencies, here are some of the ground rules for chord notation:

- A chord referred to just by its root note name is a major chord, for instance, “C”

- A chord with a lowercase m next to its root note is a minor chord, for instance, “Am”

- Diminished chords use the suffix dim

- Augmented chords use the suffix aug

- Suspended chords use the suffix sus followed by a 2 or a 4 referring to the interval that replaces the third

- Inverted chords have a bar before the lowest note in them, for instance, “C/E” refers to the first inversion of a C major chord

- Seventh chords are notated with just a “7” if it’s a minor seventh, and a “maj7” if it’s a major seventh, for instance, “Cmaj7” is a C major chord with a major seventh, and “C7” is a C major chord with a minor seventh

- C major chords with a minor seventh are also referred as “dominant chords”

- Upper extensions such as ninths, eleventh, or thirteenth are notated with a 9, 11, or a 13. For instance, C9, C11, C13

- However, if a chord skips one extension the next present ones should be preceded by “add”. For instance, Cadd9 is a C major chord without any kind of seventh, but with a major ninth

- Ninths and thirteenths by default are major, unless preceded by a “b”

- Extended chords with a major seventh should add the “maj” suffix. For instance, “Cmaj9” has a major seventh and a major ninth, while “C9” has a minor seventh and a major ninth”

- Extensions and fifths can be altered by a preceding “b” making them a semitone lower or “#” making them a semitone higher

- Generally, these alterations are presented in parenthesis after the chord. For instance, C13 (#11)

Scales

Getting a good grasp of scales and how to use them will benefit your playing a lot.

It is perhaps one of the most important music theory concepts I wish you could take away from this guide, so I’ll try to make it as easy as possible.

Scales are just lists of notes that sound well when played together.

“Together” as in chords, or using them to craft melodies.

Specifically, scales consist of 7 notes, and the rule of having one of each note “name” also applies here.

As you might have heard, there are major and minor scales, and this is defined mainly by the quality of the chord that corresponds to the tonic, or key (or first note) of the scale.

Although songs can use more than one scale, in western music we only use one scale at a time, and most songs, especially pop songs, use only one scale in their entirety.

So if you figure out the scale in which a tune is written you will know exactly which are the 7 notes that will sound great over it.

Major scale

The major scale will be our starting point, let’s lay down the notes for a C major scale so we can look at them clearly.

| C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

If you remember what we learned about intervals, you will notice that starting from C each of the other notes is at a particular distance (interval) from it, and this is not random.

Let’s see these intervals:

| C | Major 2nd | Major 3rd | Perfect 4th | Perfect 5th | Major 6th | Major 7th |

The good thing is that if you replace the starting C with any other note and take those intervals from it, you will end with the major scale for that other note.

Also, as a guitar player, you will learn that each interval has a particular shape in the guitar, making them very easy to find.

You probably already know where to find the perfect fifth and octave of any note.

Hint: It’s the shape for power chords!

Now, if you want to figure out the chords from this scale it’s super simple.

You just pick a note, skip the next one, pick the other, skip one, and pick the other.

Let’s say we want the notes for the first chord of the scale:

We pick C, skip D, pick E, skip f, and pick G: C E G, which is a C major chord.

Do it for every note and you will get:

And another important thing to notice is that the chord qualities for the chords you end up with will be the same no matter which note is your starting point.

This is why functional notation (roman numerals) is so useful to remember.

Let’s say someone asks you to jam in the scale of F major.

Once you figure out the notes (which you can probably do with the basic shape you probably know in the guitar) you will know that for instance, the fourth and fifth chords are major, while the second, third and sixth are minor.

This is great since it means that you only have to remember the “form” of the scale, and not the major scale for each of the 12 notes.

Minor scale

Just like major scales, minor scales have their own recipe, and what gives them their name is that the first chord you can build with them is a minor chord.

Here’s the A minor scale:

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

Do you notice that these are the same notes as the C major scale?

They’re just arranged differently.

In music different scales that share the exact same notes are called relative scales.

And the good news is that every major scale has a minor relative, and yes, it’s always the sixth note from the tonic of the major scale.

But are C major and A minor the same thing?

Well, not really.

When you are playing the C major scale the chord progressions you will use will, in most cases, land in C major as a resting point. Everything revolves around it.

When you are actually playing in A minor, things revolve around the Am chord.

It’s subtle, but it’s a difference, believe me.

The intervals for the minor scale are the following:

| A | Major 2nd | Minor 3rd | Perfect 4th | Perfect 5th | Minor 6th | Minor 7th |

And the chords are:

| Functional notation | Chord | Chord notes |

| i | Am | A C E |

| iiº | Bdim | B D F |

| III | C | C E G |

| iv | Dm | D F A |

| v | Em | E G B |

| VI | F | F A C |

| VII | G | G B D |

Again, you take any starting note, figure out the rest of the notes of the scale, and the chord qualities will be these.

I promise.

Pentatonic scales

Pentatonic scales are very popular in blues and rock, but these are no new scales in themselves.

Just as the name implies (penta means five in Latin) they are 5-note scales, but not any random 5 notes.

The major pentatonic scale is a 5-note version of the major scale, and so is the minor pentatonic with regards to the major scale.

Let’s look at the C major pentatonic scale:

| C | D | E | G | A |

In terms of intervals we have:

| C | Major 2nd | Major 3rd | Perfect 5th | Major 6th |

The minor pentatonic relative to C major, as you can imagine is A:

| A | C | D | E | G |

With intervals

| A | Minor 3rd | Perfect 4th | Perfect 5th | Minor 7th |

Pentatonic scales use the chords from their “complete” major and minor counterparts and are mainly used for creating melodies and solo parts.

Other scales

There are many other scales you will find in the wild, but I can assure you that if you understand major and minor scales you will have 95% of western music within your grasp.

Two other very common scales you might have heard of are the harmonic minor scale, which replaces the minor seventh interval for a major seventh, and the melodic minor scale which has both a major sixth and a major seventh interval in it.

These are out of the scope of this lesson, but with what you learned here you will easily understand how to get their notes for a certain key, and their chords.

There’s also what’s called the “blues scale” that’s just a pentatonic scale with an extra note.

Chord functions

As I hinted earlier for scales revolving around their first chord, chords within them have certain functions.

There are 3 main chord functions:

- Tonic

- Sub-dominant

- Dominant

A tonic chord is a chord that feels like home, where you are expected to start or end.

Sub-dominant chords add a little spice or direction, but not so heavily.

Dominant chords create tension and want you to go to a tonic chord for resolution.

Here are the chord functions for the major scale in functional notation:

| I | ii | iii | IV | V | vi | viiº |

| T | SD | T | SD | D | T | D |

And for the minor scale:

| i | iiº | III | iv | v | VI | VII |

| T | SD | T | SD | D | T | D |

As you can see, functions are similar, but if you try them out you will find out that the minor scale dominants don’t pack such a punch as the ones from the major scale.

This is why it’s very common to replace the fifth minor chord of a minor scale for a major chord, creating more tension towards a resolution or rest point.

This fifth major chord is borrowed from the harmonic minor scale if you are interested in the details.

Transposing

Transposing is the concept of moving music from one key to another.

As you know by now, all scales are built in a relative fashion, so if you just were to grab all the notes from a song and shift each of them uniformly by the same amount of semitones, you will end up in the key (scale) that corresponds to that movement.

Say we transpose a song that’s in C major up by 2 semitones, we will end up with the same song, but in D major.

If we were to go down by 1 semitone, we would have ended up in B major.

This is basically what playing with a capo on a guitar does. You still play the same chord shapes, but you are transposed up by the number of frets (semitones) you decided to put the capo in.

Most people can’t notice if a song is in a certain key, and there are no “correct” keys.

Singers usually transpose songs because some keys fit their voices better.

Modes

You might have heard about modes at some point but never sat down to learn them properly.

The good news is that you can live a normal life without knowing them, however, I think they have something extra to offer you in terms of freedom when thinking about music.

Dumbing things down, as is the intention of this article, modes are just slight variations of both the major and minor scales that give them a slightly different flavor.

Most common modes

The most common modes out there are those called the Greek modes.

A confusing way that many people use to teach them is by showing you that there are 5 relative modes to the C major (or A minor) scale:

- D Dorian

- E Phrygian

- F Lydian

- G Mixolydian

- B Locrian

Each of these modes uses the same notes (A, B, C, D, E, F, G) as C major and A minor.

C major is also called the Ionian mode, and A minor is the Aeolian mode. It’s just a fancy name for the good ol’ scales we already knew.

If you were to analyze the first chords of these modes you would find out that Dorian and Phrygian are minor modes, while Lydian and Mixolydian are major modes.

The odd one out is the Locrian mode which has a first diminished chord.

But, I think modes are better understood if we just fix the key.

Let’s see examples using the key of C for major modes and A for minor modes:

| Mode | Notes | Original scale variation |

| C Lydian | C D E F# G A B | #4th |

| C Mixolydian | C D E F G A Bb | b7th |

| A Phrygian | A Bb C D E F G | b2nd |

| A Dorian | A B C D E F# G | #6th |

| A Locrian | A Bb C D Eb F G | b2nd, b5th |

As you can see, a clever way of thinking about modes is that they are just different kinds of major and minor scales that alter a single note.

Two notes in the case of Locrian.

Making sense of modes

Since modes are just a way of spicing your sound up, they are commonly used to improvise or get certain feelings out of compositions.

Of course, each mode has its set of chords, which I encourage you to figure out with what we learned.

Another feature of modes is that for a piece of music to sound like a specific mode it’s important that you clearly express it.

A way of doing it is by just repeating and showing the “spicy” note of the mode very often in the music, and also making it extra clear what the “home” chord is.

In the case of Locrian, since its first chord is diminished, and diminished chords are unstable, for it to have a “home” chord it’s substituted for a B minor chord.

Modal interchange

Modal interchange is a more complex but useful concept that can be easily simplified.

Since modes are slight variations of an “original” scale, they don’t share the exact same chords.

A modal interchange is when you borrow one of these foreign chords from another mode and bring it briefly to a composition in a mode where it’s not native.

For instance, you could have a piece of music that revolves around C major, but for a single bar, you borrow a D (major) chord from the C Lydian mode (In C major D is a minor chord).

The important thing is to make evident that this was just a one-bar (or half-bar, or the amount that makes sense in the tune) thing.

A way of doing so is by quickly going next to a chord that incorporates the natural version of the shifted note in the mode from which the foreign chord was taken.

In the example, the foreign note is the F# in the D major chord, so would need to show an F to the listener via the melody or a chord that uses it.

This is a great way of spicing your music and pulling the attention of the listener by presenting something that feels slightly off.

The trick here is to not get carried away with the trick and use it sparingly.

Modal interchange is not a technique limited to modes, but to parallel scales in general.

Parallel scales are those that share the starting note, but have at least one different note.

Tying it all together

The most important thing to know about music is that if it sounds good, there’s a theoretical way of making it make sense.

And even if t doesn’t sound good there probably also is a way of justifying it.

Knowing music theory, in my opinion, will never limit you, but make you a more professional player with more tools in the belt to solve creative problems.

Can learning music theory hinder your creativity?

Some people might argue that this knowledge might limit them, but if it does it’s because they are doing things wrong.

I wouldn’t look at composing music from scratch from a theoretical angle, I’ll just let it flow.

But when I’m searching for a specific sound or a way of conveying certain emotions, going to the theory toolbox is a lifesaver.

How much more music theory is out there?

A lot.

You can get a Ph.D. in music theory if you were heavily invested in it.

But I don’t really think it will necessarily make you a better musician.

I do think that knowing the basics that I laid out here will help you a lot, and it’s a solid base on which you can rely for years, or even for life.

For a fact, I know that a lot of guitar legends we look up to knew fewer things about music theory than those written on this page.

Where to go from here?

If you want to expand on your theoretical knowledge of music I encourage you to do so, however, after having a grasp of what’s in this article, I’d rather move to its applications.

Here are the most important ones, in my opinion.

Ear training

Trained musicians do a lot of ear training which entails recognizing chord qualities and extensions by just listening to them, as well as chord progressions and intervals in melodies.

Think of the superpower it is to just listen to something and then be able to play it on your instrument.

And no, this is not something only those gifted with absolute pitch can do.

Every one of us has a different kind of ear, a relative ear, that when properly trained can us to do so.

Improvisation

Just coming up with music out of thin air is one of the better things about being a musician.

And this is also that can be trained and studied.

The rabbit hole here also goes deep, and there’s a lot to learn and practice.

Hello there, my name is Ramiro and I’ve been playing guitar for almost 20 years. I’m obsessed with everything gear-related and I thought it might be worth sharing it. From guitars, pedals, amps, and synths to studio gear and production tips, I hope you find what I post here useful, and I’ll try my best to keep it entertaining also.